WHEN the National Trust took on Hanbury Hall, near Droitwich, in the 1950s, the aim was to save the paintings of Sir James Thornhill – the celebrated 18th century English painter whose murals adorn the walls and ceilings of many of the country’s finest buildings including St Paul’s Cathedral, Chatsworth House and Blenheim Palace.

His vast paintings can be seen on the ceilings of the staircase, the hall and other rooms at Hanbury Hall and are admired by the thousands of visitors to the property each year.

However, while the National Trust focused its attention on preserving these magnificent arts works of lavish mythical scenes, it did not realise it was sitting on a rare hidden asset giving it an elite status among English county houses.

Hanbury Hall was built at the beginning of the 18th century by the wealthy chancery lawyer Thomas Vernon. According to Hanbury Hall’s visitor experience project manager Sian Goodman, the house was his summer residence as he lived in London the rest of the year.

His work and society life meant he was well connected in the capital and it is thought these associations led him to employ the most eminent garden designer of the time, George London, to create the grounds at Hanbury.

London was a pupil of the royal gardener John Rose and also studied his trade at the Palace of Versailles, where the formal layout represents man’s control over nature. He established the celebrated Brompton Park Nurseries in South Kensington with Henry Wise and went on to design gardens and supply the plants for some of the most prestigious properties in the country.

“He used to cover 60 miles a day on horseback. He went all over the country designing gardens. He also supplied the plants they wanted and then went back six months later to see how it was developing,” said Sian.

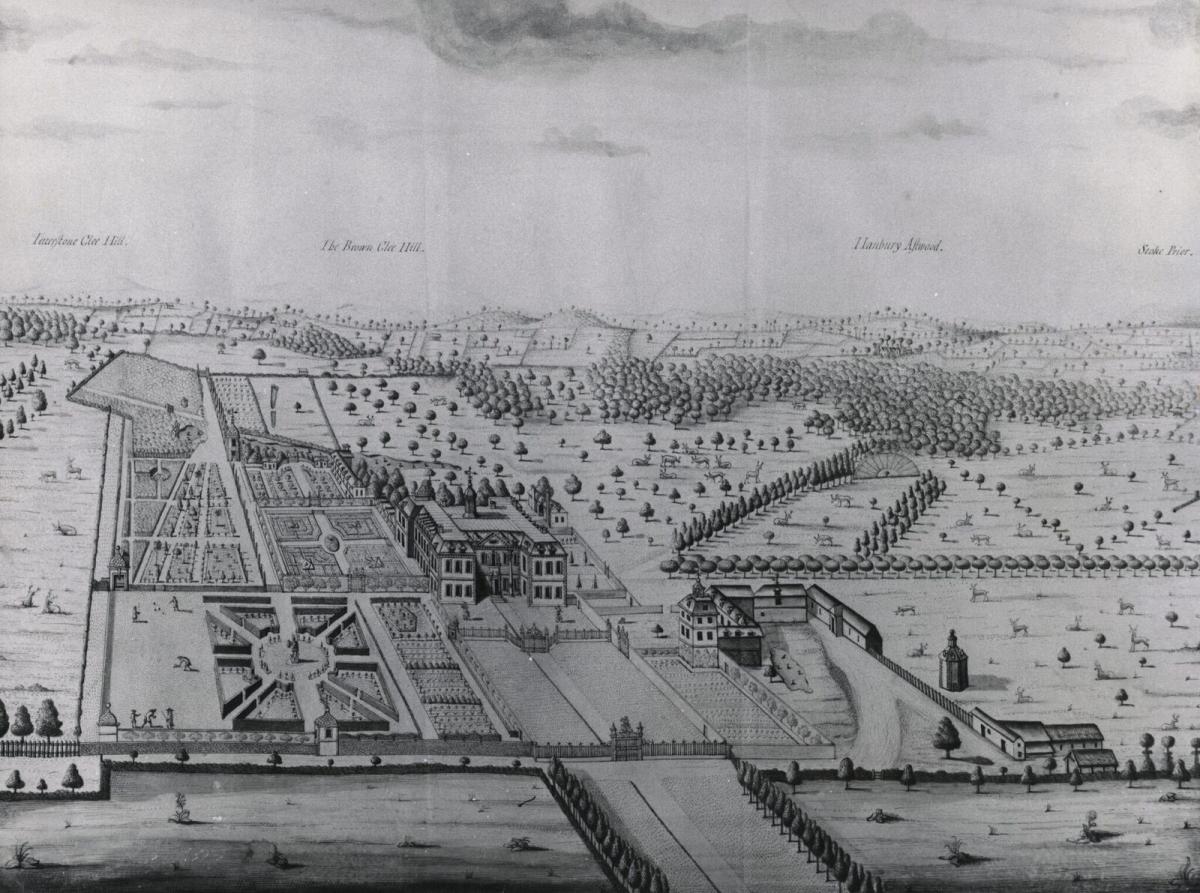

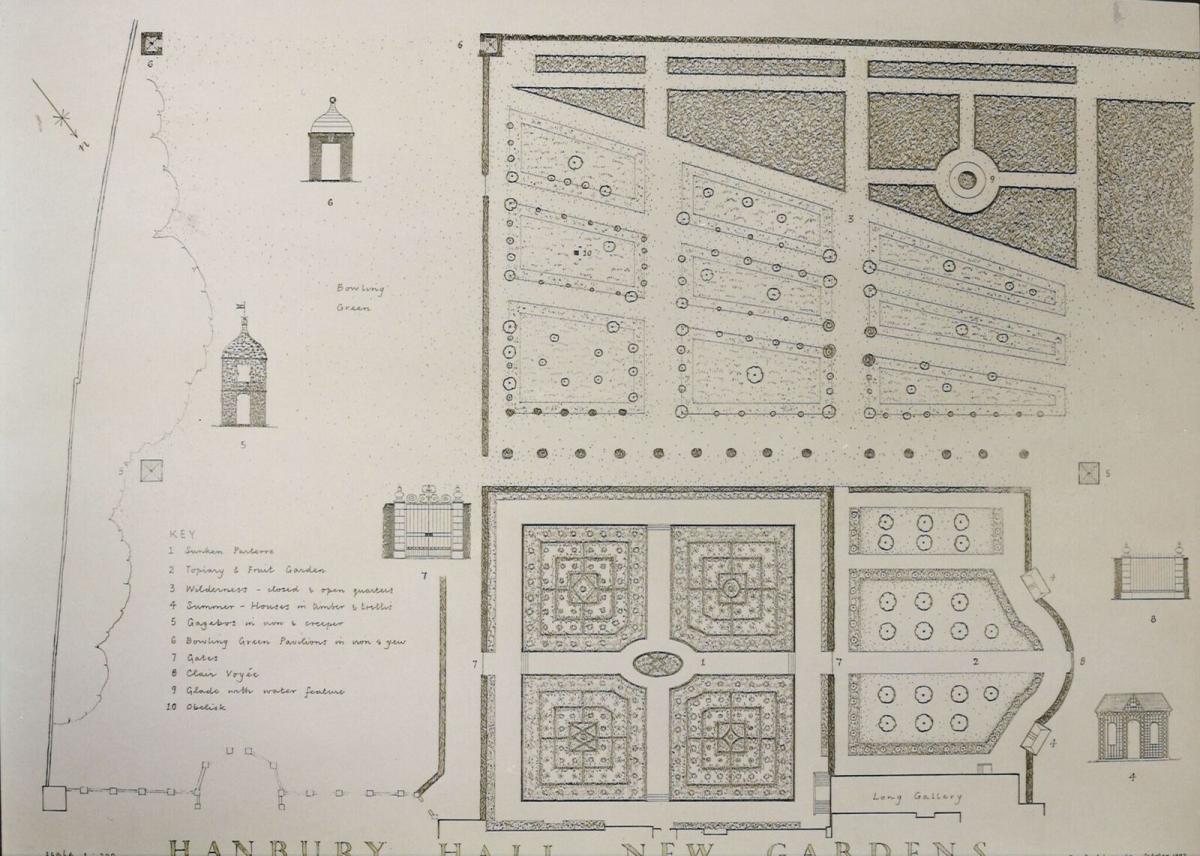

London’s garden layout at Hanbury Hall with its sunken parterre formal garden, a topiary and fruit garden offering vistas across the surrounding countryside, a bowling green, wilderness area and other features like the summer house and gazebos indicates the start of the landscape movement for which Capability Brown became renown.

Towards the end of the 18th century the grounds around the house were put to lawn and by the 1950s when the National Trust became involved with the hall, there was no trace of the ornate planting and design or clues to this prestigious heritage.

But about 28 years ago a farsighted gardener Neil Cook – who only planned to stay for a couple of years to further his professional experience – was appointed and recognised the lost legacy.

The lone gardener at Hanbury began work to return the grounds to their former glory. Original plans found at Worcestershire Records Office, maps, paintings and archaeological and geophysical research were used to discover the scale and position of the original garden features.

Neil worked with a team of experts defining, with mathematical precision, the layout of the topiary and hedge framework. They also used the original Brompton Park Nursery historic planting guides to select the most appropriate specimens.

Sian said: “The re-created garden was officially opened 21 years ago and since the gardening team at Hanbury has lovingly and patiently maintained this restored historic gem.”

Most of London’s gardens, including the formal gardens at Chatsworth, were swept away when the English Landscape movement became fashionable later in the 18th century. Sian explained that during periods of political uncertainty, formal gardens gave people a sense of order, structure, safety and control over their immediate environment.

As the wider world became more stable, garden fashions changed and people relaxed their grip on trying to control their garden environment, which was also high maintenance and expensive to keep, to allow nature to takes its course more freely.

Sian believes the mixture of formal and wild areas at Hanbury Hall were the first steps towards the landscape movement. “This is a really magical moment in history,” she said.

“Today, Hanbury is one of only three gardens where people can experience London’s work,” she added. The others are the Privy Garden at Hampton Court Palace and the garden at Melbourne House, Derbyshire.

“Hanbury was designed as a special 18th century pleasure garden and now, thanks to generous investment, the team at Hanbury Hall and the National Trust, it is there for everyone to enjoy.

“At Hanbury Hall visitors can enjoy the same pleasures and recreation in this special place - escaping for a while and leaving behind the pressures and conflicts of everyday life - just as George London had intended,” said Sian.

Back in the 18th century the gardens were not just a place for relaxation, they performed another job in providing food for the house. She explained that fruit from the clipped trees would have been taken to the summer house and would have been over wintered there, while the vegetable garden would have supplied the house too.

The official opening of the re-created gardens 21 years ago marked the first part of a larger project. Over the years Neil and his growing band of helpers – now three full-time gardeners, two part-time gardeners and 90 volunteers – have gradually extended the restoration further from the house.

Neil said: “My aim was only to be here for a few years and then move on to something more exciting and bigger. This has been fascinating for me and we have not finished. It is so nice to see the place loved so much and to see so many people coming to enjoy it.”

Last year London’s novel viewing platform was reinstated. It is thought to be the earliest example of the “borrowed landscape” – where views are used to give the impression of a much larger estate – in a formal park setting. It illustrates how London anticipated the landscape garden movement, which ultimately resulted in the destruction of so much of his work.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel