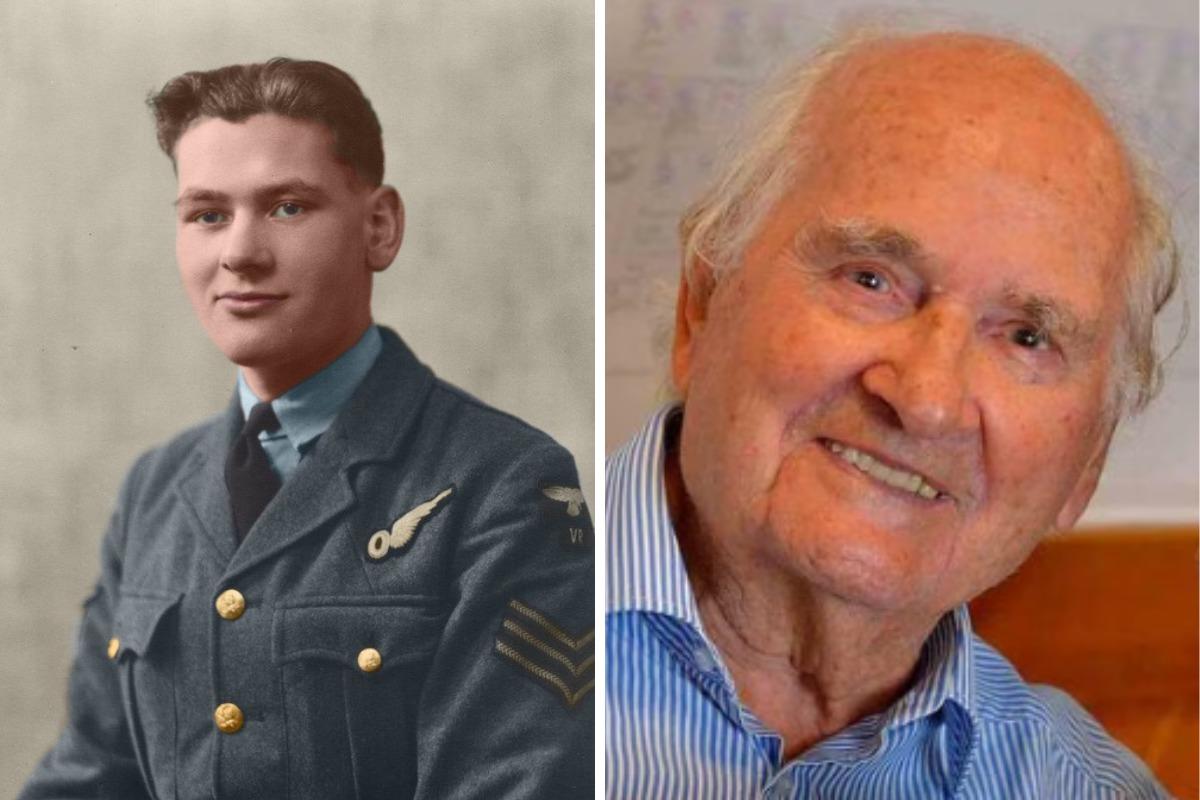

THERE must have been times in 1943, adrift in the English Channel in a leaky dingy, when Ron Tomlin didn’t think he’d see the end of the Second World War let alone live to be 100.

The first was achieved thanks to some remarkably compliant German prison camp guards and the second will be ticked off on next Tuesday (Sept 12) with a party in the Droitwich care home where he now lives. Adding to the celebrations will be a family occasion at his son David’s home in Martley on Sunday.

Born in Birmingham, Ron was too young join the services when war broke out, so he joined Home Guard and then the Air Defence Corps (now the Royal Air Force Cadets), which helped pave the way to being selected for the RAF when he was eventually called up.

He was a 19-year-old sergeant bomb-aimer in 10 Squadron RAF, which took part in raids over Hamburg and Nuremberg in August, 1943. The first two over Hamburg went fairly smoothly, but on third the bomber developed an engine problem, which the crew reported on their return to base in England.

Ron said: “We assumed our Halifax was out of action and so we went to bed at 4am. But suddenly we were woken up and told there was nothing wrong with the plane and we were going to Nuremberg, so we were on operations two nights in a row.”

The journey to Nuremberg took eight hours, and on the return journey during the early hours of August 11, the engine problem recurred. A second engine on the opposite side of the plane also developed a fault.

The plane lost height as it flew over Dieppe, descending to 9,500ft, making it a sitting duck for the enemy. Gunfire duly arrived as it descended over the English Channel, damaging the inflatable lifeboat. The crew were forced to make an emergency landing on water, and patch the dinghy as best as they could.

Ron added: “When we ran out of patches, we had to put our fingers in the holes, we were pumping all the time to keep the boat inflated, We were in the sea for about 17 hours, before the Germans caught us.

“We had swallowed a lot of oil, and had been vomiting all the time. I don’t know how the other crew members were feeling, but I was quite glad to be rescued by a German boat. Had we not been captured, we would have probably ended up in the North Sea, which is much more difficult to be rescued from.”

Four days after their capture, they were sent to the Gestapo headquarters at Dulag Luft for interrogation. It was something Ron had been prepared for by his RAF training.

He explained: “We had been told what to expect, they would move you from hut to hut, Some nights they would put you in the same hut as one of your crew, another they would put you in with a stranger.

“The important thing was you never talked about anything, because if you were talking to your crew mates, somebody might have been listening, and if you were with a stranger they might already be collaborators. It wasn’t pleasant, but apart from them sometimes waving guns about, there was never any violence from them.”

Ron was then transferred to Poland, finishing up at the Stalag Luft IV camp until the Russian advance of February, 1945. As the Russians moved closer, the prisoners were ordered to march 500 miles on foot back to Germany, often being expected to complete 30 miles a day. On reaching Fallingbostel in Saxony, Ron and his pilot refused to march any farther until he had his frost bitten foot operated on, so just they stayed put.

“Most of my crew went with the other prisoners, “ he said, “but Dibben, the pilot, and I went into sick bay, lay on the floor, said we were too sick to move and stayed there. We knew the Army was getting close because we could see the searchlights in the sky.”

Remarkably Ron’s German captors made little effort to coerce them and simply left the pair behind. They were liberated two days later on April 16, 1945, by the advancing British forces. He maintained on the whole, the men were treated fairly by the Germans, adding: “They were just doing their job.”

After being liberated Ron was flown back to England where he was treated at RAF Cosford hospital for dysentery and returned to his mother’s house in Birmingham by VE Day. Back on Civvy Street, he trained as a draughtsman.

Ron’s centenary celebrations have been co-ordinated by John Mason, president and voluntary welfare officer of the Worcester and Districts Royal Air Force Association, who said: “As a veteran of Bomber Command myself it has been a great joy and honour for me to be able to be a friend to Ron and to see that the RAF of today is able to show its gratitude for the sacrifice he made for us back in WW2.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel