Earlier this month the Worcester News reported how former soldier John McClay and two friends marched 15 miles to raise funds for the Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen and Families Association (SSAFA) Forces Help, a charity for service and ex-service personnel.

Mr McClay was inspired to help after the charity supported his struggle to cope with post-traumatic stress disorder, which he developed after serving in the Balkans. Here he recalls the horrors of a war that will haunt him forever. Some people may find parts of this interview distressing.

FORMER soldier John McClay has witnessed countless horrors but the beautiful face of the murdered child in the red coat burned its way into his brain like a brand.

No amount of drink or pills could wash her out and for years she remained, emblazoned there, beyond his help, buried under the bodies of her slaughtered family in the smouldering ruins of a burnedout house in a little village on the edge of Kosovo’s capital city, Pristina.

Wherever he turned, even years later and back on British soil, there she was with her dark hair, her red coat and her open throat, murdered by the Serbs before her life had really begun.

Mr McClay, aged 43, of Larkspur Drive, Evesham, who served with the Irish Guards, found the memory gained an ominous power following the birth of his daughter, now 10 years old.

He said of the murdered girl, an ethnic Albanian: “She was only six or seven years old. Her family had been killed and her throat had been cut.

“She had long black hair and a little red coat on. She had her whole life to live and it was taken away by some evil person who cut her throat just because of her religion.

“After I had come back home my ex-wife bought my daughter a red coat. I wouldn’t allow her to wear that red coat.”

Mr McClay, the son of a paratrooper, joined the Irish Guards in his 20s because he wanted a better life and to get out of Evesham, the town where he was brought up.

He was stationed in Northern Ireland in 1997, keeping the peace between Catholics and Protestants during the notorious marching season.

He and his friends held the line with shields and batons while they were pelted with petrol bombs, bottles and bricks. They lived on a knife edge, fearing snipers or car bombs, scanning the perimeter, checking equipment and rechecking it, manning the observation posts, marked out by the uniform, the haircut and the accent as an outsider – and a target.

Some of his friends suffered burns in such attacks, their cotton and polyester gear affording limited protection when it caught fire and melted onto their skin.

But his journey into the heart of darkness was only just beginning.

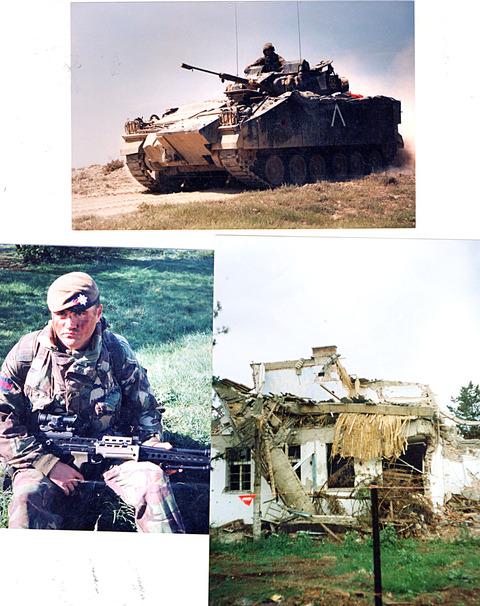

He was called out with the Guards to Kosovo in early 1999, joining the King’s Royal Hussars in Macedonia where he heard the bombing raids which were supposed to clear the way for the infantry’s advance.

The bombing, he says, failed to soften up targets such as roads and bridges or disrupt Serbian supply lines mainly because the Serbs proved so effective at creating dummy targets to protect their military hardware and infrastructure.

The battle group’s advance into Kosovo began in June 1999, after the Serbs had signed an agreement to withdraw, and guardsman McClay witnessed the full horror of genocide on an unimaginable scale.

He said: “We went into the chamber of horrors, the Serbian police station in the centre of Pristina. They had photograph albums of dead kids, photographs of women being raped. People were holding up heads, children’s heads, like they were holding up a fish.”

They confiscated a huge arsenal of weapons – AK47s, pistols, Dragunov sniper rifles, machetes, knuckle dusters, even weapons from the Second World War.

They advanced in the shadow of Arkan’s Tigers, the paramilitary murder squads led by eljko Ranatovic, to find houses looted and burned. Inside were whole families of ethnic Albanians murdered by Serbs and sometimes Serbs murdered by Albanian guerrillas.

He said: “We weren’t equipped to deal with mass genocide. The Serbs were retreating and burning houses as they went.

“They were stealing cars and they were raping women and they were doing it in front of us.

“To begin with our orders were not to do anything. If we had opened fire on the Serbs we would have been done for war crimes.

“We were fishing bodies out of the river at Pristina. Serbs had killed them and just dumped them.

It was no job for the infantry.

There were bodies all over the place, in every house.

“You found mounds of dirt.

“Whole villages were massacred, from elderly to newborn babies.

“Some guys were already starting to get nightmares. You couldn’t get rid of the smell of death. The smell of rotting flesh was everywhere, in the drains and in the culverts.”

Once he stepped over a barbed wire fence and onto a corpse rolled inside a carpet, releasing the sickening stench of decay.

Similar scenes greeted him on the tour for the next seven and a half months.

He said: “This was humanity at its worst – ethnic cleansing. Here the price of a human being, the life of a human being, was less than a can of Coke. It is beyond comprehension that people can do this to other human beings. As a soldier you expect to take a life or to pay the ultimate sacrifice yourself. That’s soldiering.

“If you’re not prepared to do that, you shouldn’t have joined up. But we had to pick up after the aftermath of it all. That’s not what soldiers do.”

The bodies they found were taken to a makeshift mortuary in Pristina. Once they had to shoot a dog that had been gnawing on the body of a man before it made off with his leg.

Mr McClay served nine years with the Irish Guards and six years with the Royal Military Police where he excavated mass graves in Bosnia in the hunt for evidence to bring war criminals to justice and identify the victims of atrocities.

In total he has completed 10 operational tours of duty.

He hurt his back when a military vehicle was damaged by a mine in Bosnia in 2003 but the psychological scars run deepest.

“The worst scars are the ones you can’t see. When you come home you could have lost a limb.

“You could have physical scars but no one can see your mental scars. People don’t understand because it’s not a visible injury or illness.

“The first thing many soldiers want to do when they get home is get wasted. You want to try and forget. It’s a coping mechanism. It’s to block it out. I have done it myself.

“With alcohol you’re just burying the problem but it will come back again. GPs just tend to give you anti-depressants and say, ‘See how that works’. It doesn’t work.”

Servicemen must also weather the sometimes ignorant and insensitive comments of civilians with no notion of such horrors or the crushing sense of guilt they feel.

“People say, ‘Nothing much happened in Bosnia’. How do they know? Were they there? I never got any help when I came back. You just got told to ‘crack on’ or ‘man up’. You can be the strongest mind in the world but there is only so much you can take before you break.”

Mr McClay was diagnosed as having post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by his GP in November last year.

He was referred to Dr David Muss, director of the posttraumatic stress disorder unit at BMI The Edgbaston Hospital since 1991, after support was provided by the Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen and Families Association (SSAFA) Forces Help.

There he learned the rewind technique to place some of the horrors in his long-term memory where they are less able to torment him in the present.

Triggers for PTSD included the smell of meat being grilled on a barbecue or at a butcher’s which brought back the smell of dead and burning flesh, war films or the scent of germolene which reminded him of smoke grenades and phosphorus grenades.

He packed away his war medals and his photographs. PTSD robbed him of his ability to sleep and his appetite. He lost weight. His marriage broke down. He suffered mood swings, mental breakdowns, sweats, nightmares and contemplated suicide, a path some of his friends had already chosen.

Guardsman McClay knows at least 15 soldiers who are dead, either killed in action or from taking their own lives. He has carried the coffins of friends killed in Iraq in 2003.

He said: “Since I have had my treatment I feel that I need to put my ghosts to bed and a lot of my ghosts have gone. They are still in my memory but they’re not tormenting me anymore. I can see a child with a red coat and it doesn’t affect me. I don’t have the guilt.”

SUPPORT FOR OUR HEROES

THE Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen and Families Association (SSAFA) Forces Help is the UK’s oldest Armed Forces charity, providing practical help and assistance to anyone who is currently serving or has ever served, even if it was only for a single day.

Each year they support more than 50,000 people in the Armed Forces community.

John McClay, Eddie Fray and Adrian Nash completed a 15- mile march carrying a 14kg pack from the SSAFA office in Worcester to Evesham on August 11, so far raising more than £1,000 for the charity.

To make a donation, send a cheque to John McClay, SSAFA Forces Help, The TA Centre, New Dancox House, Pheasant Street, Worcester, WR1 2EE. For details, call Jill Hart at the local branch on 01905 21728.

For more information about the work of Dr David Muss, visit davidmuss.co.uk.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here