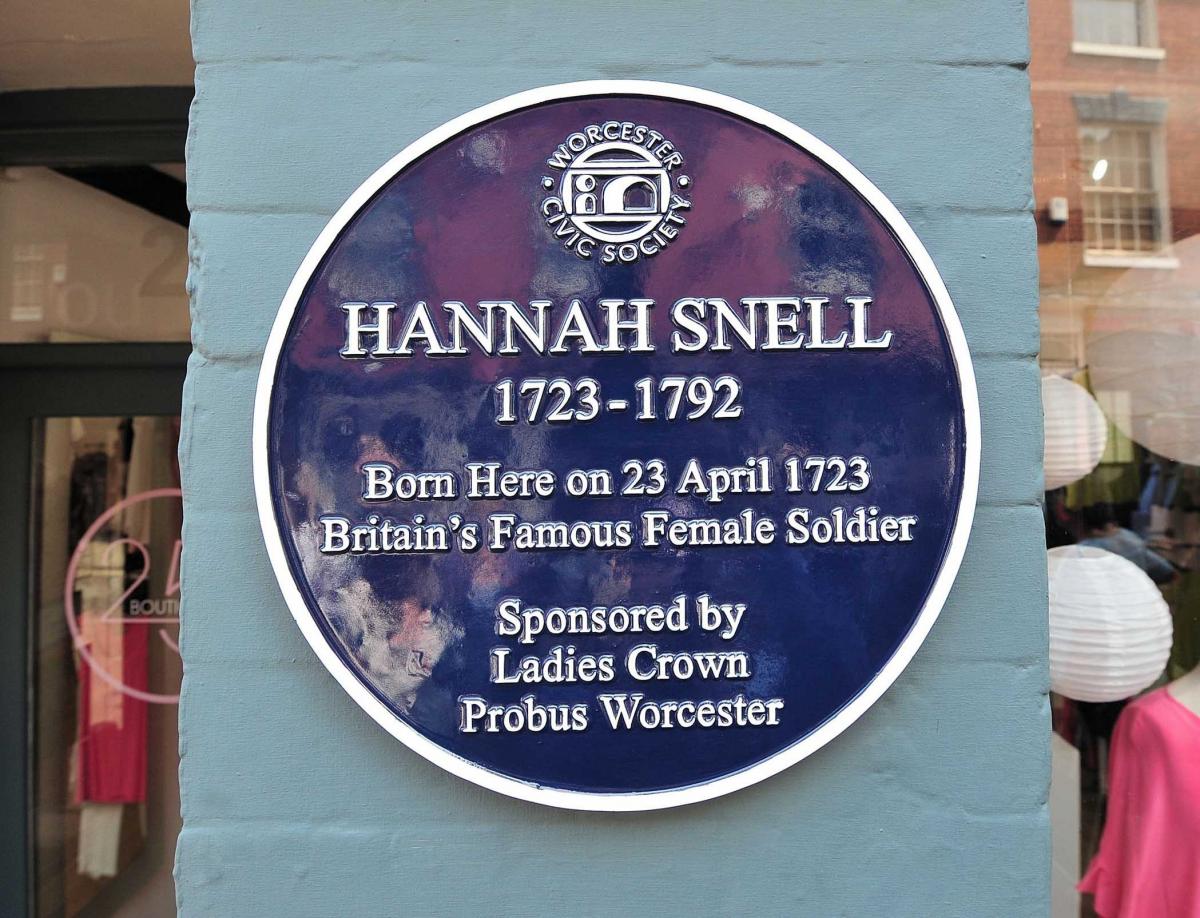

A BLUE plaque for a Worcester woman, described as 'Britain's most famous female soldier', has been unveiled by a direct descendant.

The plaque in memory of Hannah Snell is only the second blue plaque devoted to a woman in the city, the other being in honour of Alice Ottley.

However, Worcester Civic Society's leaders want to see far more of the city's women represented on the blue plaques in future but need sponsors to bring their plans to fruition so more of the city's illustrious daughters can be celebrated.

Hannah Snell is known for disguising herself as a man so she could become a soldier, was involved in several battles, survived a flogging and suffered a musket ball injury, carrying out surgery on herself to keep her gender secret.

The Worcester Civic Society had the plaque made and it was unveiled by Hannah Snell's descendant, Amanda Houston (her sixth generation granddaughter), and Matthew Stephens who has written a book about her.

Mr Stephens, a research librarian in Sydney in Australia, put Worcester Civic Society in contact with Amanda Huston.

Phil Douce, chairman of Worcester Civic Society, said: "We decided to concentrate of plaques for women as up till now we only had Alice Ottley. We have a number of suggestions already including Sheila Scott and some others, but they need sponsors."

Worcester Crown Ladies Probus Group sponsored the plaque.

Hannah Snell was born in Worcester on April 23, 1723, the daughter of Samuel and Mary Snell.

Her parents died when she was 17 and at the age of 20 she married James Summs, a Dutch seaman who mistreated her, abandoning her when she became pregnant.

After their daughter died in infancy, Hannah Snell determined to track her husband down.

Believing that he had been pressed into military service she borrowed a suit of clothes from her brother-in-law, James Gray, assumed his identity and according to her own account, became a soldier in the 6th Regiment of Foot.

With advent of the Jacobite Rising in 1746, the regiment marched to Carlisle where Hannah continued her military training.

She was often at the centre of fighting and is reported to have received a number of wounds of varying degrees.

Incurring the wrath of a sergeant on one occasion, she was sentenced to 600 lashes of the whip, a harsh punishment but after enduring 500 lashes in silence her commanding officer ordered the end of the punishment.

Believing her husband had gone south she deserted and joined Fraser’s Regiment of Marines at Portsmouth, ultimately sailing to the East Indies and India where she took part in several battles.

She eventually learned that her husband had been executed for murder in Genoa, Italy.

When the ship returned to England she revealed her true identity. Honourably discharged, she was granted a military pension and her exploits became public knowledge.

She married twice more, giving birth to two sons by her second husband and marrying again in 1772 after he died.

She was buried at Chelsea Hospital among other old soldiers.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel