TRAVELLING the A449 from Worcester to Malvern, you come to a set of traffic lights at Powick.

They are at a crossroads on top of an incline, just past the village school and where a chinese restaurant now stands high profile on the right.

To the left is a road, wider than it used to be, but still rural enough to be called Hospital Lane. The road sign is just about the only visible reminder that for more than 130 years this was the site of a huge, rambling, psychiatric establishment for the mentally ill.

Virtually all physical evidence of Powick Hospital has long disappeared. Bulldozed down and away and out of sight by developers nearly 20 years ago, to be replaced by a layout of smart modern housing with patios, neat lawns and cars on the driveways.

Only the architecturally protected main building, a red brick edifice called White Chimneys and the old hospital superintendent’s house remain. The former has been converted into apartments and the latter to offices.

Of the rest of the hospital, which had 1,200 residents at its peak, there is no sign. But for people who lived nearby or passed by and looked across at the grim complex of brick walls and little windows, there remains a fascination with the place.

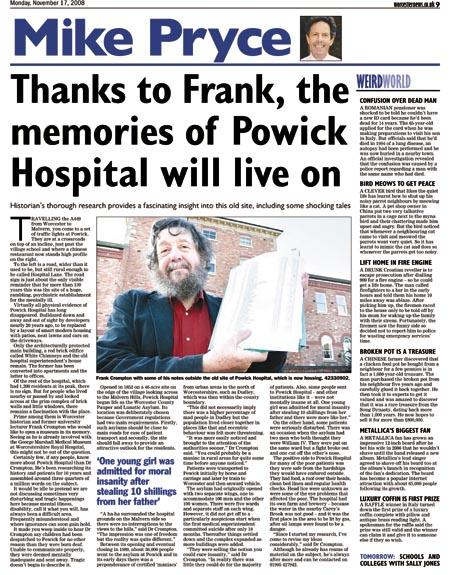

Prime among them is Worcester historian and former university lecturer Frank Crompton who would like to open a museum in its memory.

Seeing as he is already involved with the George Marshall Medical Museum at Worcestershire Royal Hospital, this might not be out of the question.

Certainly few, if any people, know more about Powick Hospital than Dr Crompton. He’s been researching its history and patients for 10 years and assembled around three quarters of a million words on the subject.

It would be idle to pretend we are not discussing sometimes very disturbing and tragic happenings here because mental illness, disability, call it what you will, has always been a difficult area.

Frequently misunderstood and where ignorance can soon gain hold.

It made you weep inside to hear Dr Crompton say children had been despatched to Powick for no other reason than they were born deaf.

Unable to communicate properly, they were deemed mentally inadequate and sent away. Tragic doesn’t begin to describe it.

Opened in 1852 on a 46-acre site on the edge of the village looking across to the Malvern Hills, Powick Hospital began life as the Worcester County Pauper and Lunatic Asylum. Its location was deliberately chosen because Government regulations had two main requirements. Firstly, such asylums should be close to main roads for ease of patient transport and secondly, the site should fall away to provide an attractive outlook for the residents.

“A ha-ha surrounded the hospital grounds on the Malvern side so there were no interruptions to the views to the hills,” said Dr Crompton.

“The impression was one of freedom but the reality was quite different.”

Between its opening and eventual closing in 1989, about 36,000 people went to the asylum at Powick and in its early days there was a preponderance of certified ‘maniacs’ from urban areas in the north of Worcestershire, such as Dudley, which was then within the county boundary.

“This did not necessarily imply there was a higher percentage of mad people in Dudley but the population lived closer together in places like that and eccentric behaviour was felt more threatening.

“It was more easily noticed and brought to the attention of the authorities sooner,” Dr Crompton said. “You could probably be a maniac in rural areas for quite some time before anyone noticed.”

Patients were transported to Powick initially by horse and carriage and later by train to Worcester and then onward vehicle.

The asylum had originally opened with two separate wings, one to accommodate 100 men and the other 100 women. There were five wards and separate staff on each wing.

However, it did not get off to a particularly auspicious start when the first medical superintendent committed suicide after only 18 months. Thereafter things settled down and the complex expanded as more buildings were added.

“They were selling the notion you could cure insanity,” said Dr Crompton. “In reality there was little they could do for the majority of patients. Also, some people sent to Powick Hospital – and other institutions like it – were not mentally insane at all. One young girl was admitted for moral insanity after stealing 10 shillings from her father and there were more like her.”

On the other hand, some patients were seriously disturbed. There was an occasion when the asylum had two men who both thought they were William IV. They were put on the same ward but a fight broke out and one cut off the other’s nose.

The positive side to Powick Hospital for many of the poor patients was they were safe from the hardships they would have endured outside.

They had food, a roof over their heads, clean bed linen and regular health checks. Head lice were unknown as were some of the eye problems that affected the poor. The hospital had its own farm and brewery – because the water in the nearby Carey’s Brook was not good – and it was the first place in the area to be lit by gas, after oil lamps were found to be a danger.

“Since I started my research, I’ve come to revise my ideas considerably,” said Dr Crompton.

Although he already has reams of material on the subject, he’s always after more and can be contacted on 01905 427942.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article