THINK of missionaries and you probably think of Dr David Livingstone’s dangerous 19th century adventures in darkest Africa and his subsequent “discovery” by New York Herald reporter Sir Henry M Stanley – in those days even hacks were gentry – who had been dispatched to find him. Their meeting produced the line “Dr Livingstone, I presume”, which has gone down in history.

You don’t necessarily think of a Worcester News journalist driving 10 miles out to the village of Guarlford, in the lee of the Malvern Hills, where most of the locals were converted to assorted versions of the Christian faith quite some time ago.

But there, in a modern house with a doorbell and a back garden, I came across Edward HB Williams, whose version of missionary work involved several years lecturing in the physics laboratory of a college near Calcutta. Up the jungle, it was not.

In truth – but certainly not to denigrate Mr Williams’ valuable contribution in India – I probably missed this family’s best story by a couple of generations because his grandfather was a pioneer Baptist missionary in The Congo. Now that would have been something.

Even so, the book Mr Williams has written about his life and experiences, called Building Bridges and Crossing Cultures (Aspect Design £10) and subtitled Memoirs of a physicist, missionary and minister sheds an interesting light on some very changing times.

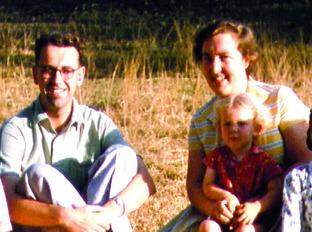

Together with his wife Rosemary, he spent the best part of a decade in India, from early 1959 until the summer of 1968, and even in that relatively brief period the social landscape shifted remarkably.

“When we left we were part of a more general exodus,” he said.

“When we arrived, we were among about 125 BMS (Baptist Missionary Society) missionaries in India, but within nine years that number had fallen to about 20.

“In 1991 there were just four.

Today there are none. That era has well and truly ended.”

Following Indian independence in 1947, the country took a couple of decades to get itself established, then things began to change.

“In 1967 the Indian government placed certain restrictions on all missionaries, requiring us to obtain special endorsement before entering or re-entering the country and to report to the police every three weeks,” Mr Williams said.

“While this latter did not present a problem in itself, it meant that the atmosphere had changed. In any case, it was time for missionaries to be withdrawing from India as there was such good Indian leadership in place.”

In fact, it was actually suggested he stay in the country, because a certain school needed his type of expertise, but the couple decided to make the break complete.

“My reply was, ‘Those days have gone’,” he said.

Their adventure had started out in the late 50s with a typical ex- Colonial flavour.

“Our last month before we left was a whirl of activity and packing,” he said.

“We worked from a list supplied by the BMS and this included the purchase of a pith helmet or topee.

However, this was never worn because by the time we got to India they had gone completely out of use, except as fashion symbols by Anglo-Indians.”

In the style of the times, Mr and Mrs Williams sailed out to India in January 1959, routine air travel still being a way off.

“We travelled on an Anchor Line ship,” he said. “It was a single class vessel, so we had freedom of movement throughout the passenger decks but missionaries, of whom there were a number, were in the rearmost cabins on the lower deck – further back than the Asian women in purdah!

“Presumably the various missionary societies all chose, quite rightly, to pay the minimum fare.”

The voyage lasted 20 days and included a rough crossing of the Bay of Biscay, sailing through the Suez Canal and stopping off at Port Said and Aden.

After landing at Bombay, there was a 40-hour train ride across India to Calcutta, which provided a wonderful opportunity to see the country. These days, flying might be much quicker, but it’s not half the fun.

The BMS sent Mr Williams to India to lecture in the arts/science department of Serampore College, which lies 11 miles from Calcutta.

With his physicist qualifications, it was a position for which he was ideally suited. Founded in 1818, the college is generally considered one of India’s greatest and most historic Christian institutions and has trained many of the country’s leaders.

Mr Williams’ account of his time there reflects the colour and contradictions of this most amazing country.

Tales of the rickshaws and ceiling fans, of the breathtaking views and the kaleidoscope sunrises and of the fact that ordered food, chicken for example, frequently arrived in the kitchen live and had to be killed.

But one of my favourites is of the staff versus students football match. The staff were awarded a penalty and the young students, by then becoming more Westernised with all their kit, watched with some amusement as the ball was given to an elderly member of the office staff, who had probably never worn shoes in his life.

He hitched up his dhoti (the traditional long garment) and waddled barefoot up to the ball, which then flew like a bullet into the top corner of the net.

As the popular Liverpool graffiti used to say: Jesus Saves, but St John scores on the rebound. Or in this case, the old Indian clerk with no shoes.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here