THERE may be no live matches of any sport to report in these crazy days of coronavirus, but how about considering for a moment who would be the most important sporting personality Worcestershire has ever produced. May I offer as my nomination Basil D’Oliveira. Certainly Basil wasn’t born here, indeed that was the whole point of his story, but it was Worcestershire County Cricket Club that gave him his chance and to whom he remained loyal throughout his first class career. During which the Basil D’Oliveira saga not only changed cricket, it changed the world.

This wasn’t something he deliberately set out to do and in some ways he was an unwilling participant in the political storm that followed his selection for the MCC team to tour South Africa in 1968-69. A storm that was to start with cricket and grow to envelop just about every other international sport as well.

How quickly the D’Oliveira Affair has passed into history is quite remarkable, because ask any sports fan under 50 today and they simply could not envisage a situation in which a South African cricket team would refuse to play one from the West Indies, India or Pakistan because of their colour. But that’s how it was before Dolly came along.

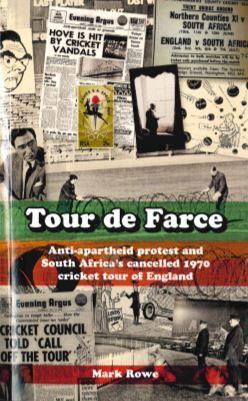

The whole shebang has been covered in considerable detail in a remarkable new book by cricket historian and journalist Mark Rowe, who in the course of 330 pages reveals details about the political shenanigans and behind closed doors goings-on that may not have been known before. He takes as his focus for “Tour de Farce” (ACS Publications £18) the abortive attempt by a South African cricket team to tour England in 1970. But in reality its scope is much broader than that. Because it covers the ground that led to that pivotal summer and what followed.

Basil Lewis D’Oliveira was born into a family of Indian-Portuguese descent in Signal Hill, Cape Town, South Africa, officially in 1931, although the date may be fluid because it was often thought in later life he knocked a few years off his age. By the time he reached his late teens the country had adopted the apartheid system of government, which separated the population on racial grounds. No players of colour could represent the country’s national teams and South Africa did not allow what they termed “coloured” teams to tour there. However Dolly soon proved himself a talented sportsman - he captained South Africa’s national non-white cricket team and also played football for the non-white national side – and when he was spotted by renowned English cricket commentator John Arlott in 1960 and urged to take his chance in the UK, the fuse was lit for the explosion that was to follow a decade later.

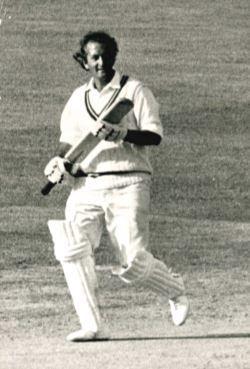

Dolly played for Middleton in the Central Lancashire League for a few seasons before joining Worcestershire CCC in 1964, his swashbuckling batting and canny medium pace bowing soon making him a crowd favourite. By 1966 he was playing for England.

So the scene was set for that tour to South Africa over the winter of ’68-’69. Although undoubtedly worthy of selection, Dolly was not chosen initially, but when Tom Cartwright of Warwickshire dropped out his name was added to the squad and the cat was among the pigeons. It was anticipated the South African government would not allow him to line up against their national side and they didn’t. After much politicking the tour was cancelled. And so we came to the return contest in the summer of 1970. The “Tour de Farce” as Mark Rowe calls it.

It was the era of violence, vandalism and anti-apartheid protests that split society, many led by a fuzzy haired young man called Peter Hain, who later grew up to become a silver haired and smart suited Labour MP. South Africa was eventually excluded from Test cricket for 22 years - a watershed in the sporting boycott of apartheid South Africa. The D’Oliveira Affair had a massive impact in turning international opinion against the apartheid regime in the country. It prompted changes in South African sport and eventually in society. Throughout the maelstrom, Basil D’Oliveira acted with a quiet dignity. He lived in St John’s,Worcester with his wife Naomi and family and eventually died in November 2011. In September 2018 he was posthumously awarded the Freedom of the City of Worcester. That’s why Dolly CBE is Worcestershire’s most important sporting personality. In my view.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here