THOSE who adopt the rather cynical view that anyone who stands for public office does so firstly for their own benefit and secondly for everyone else’s, would have had a field day with the goings-on in Worcester in the early 1800s.

Because before the Municipal Reform Act of 1835, the city was run by a closed shop Corporation and when the system was finally overhauled this self-important body was found to be as bent as a nine bob note.

It had been an entirely self-elected group with vacancies being filled at the will of the surviving members.

When mapping was in its infancy, one of the Corporation’s duties was to maintain parish boundaries. This was done by “beating the bounds” to mark the limits. In St Helen’s a choirboy was “bumped” at the parish corners i

Therefore the vast majority of citizens had no say in local government. It was also chosen on social grounds and was generally considered “the best club in Worcester”. Civic banquets were frequent, the costs being met from council funds.

The Corporation consisted of two groups, the Twentyfour and the Fortyeight.

The first were the inner circle of the old self-elected corporation, a system which continued until relatively recently with the office of alderman.

Read more: Could Worcester be the United Kingdom's oldest settlement?

The Fortyeight, or common council, were similar to today’s councillors, except things were run on closed shop lines and no “reformers” were allowed in.

Each group had its own special rendezvous. The Twentyfour met at the Globe in Powick Lane, while the Fortyeight met at the Talbot on The Cross, which later became a bank, then a club and then the Westminster Bank, now NatWest.

Later the Fortyeight moved to the Pheasant in New Street where they had their own bowling green and cock fighting pit.

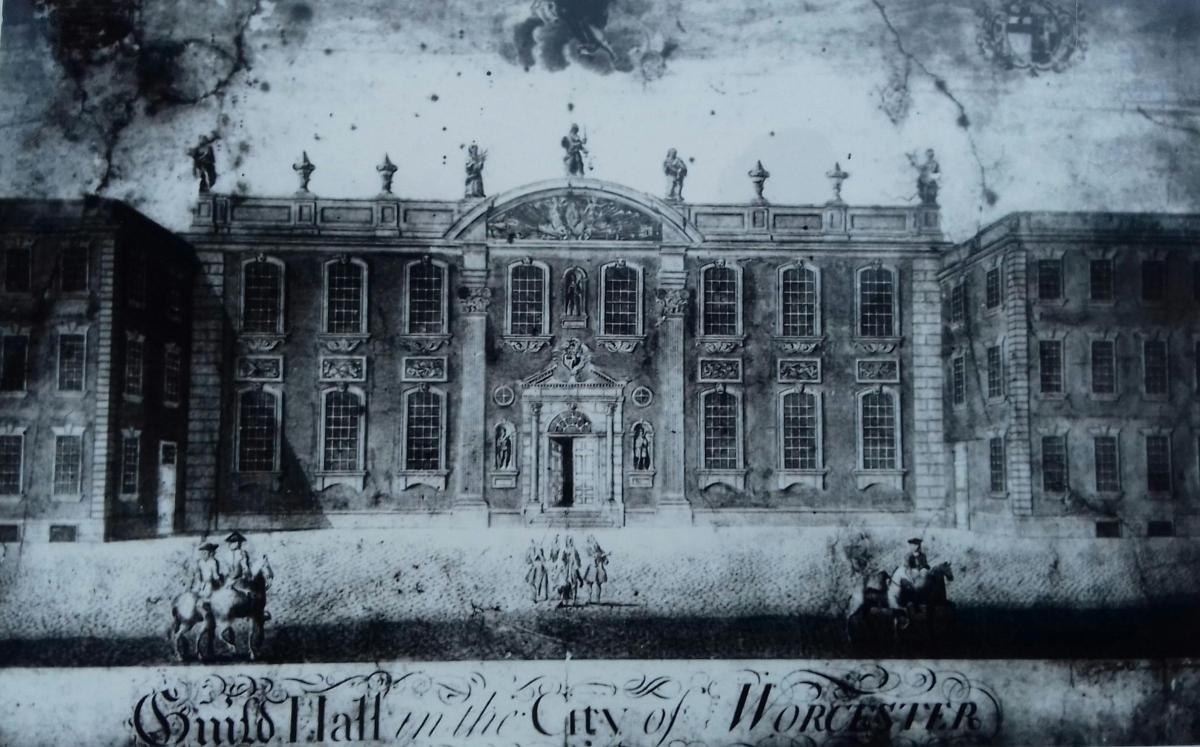

The Guildhall courtroom. Both county and city courts were held there until the Shirehall was built in 1835

However at the elections following the 1835 Act, the fertiliser hit the fan. With the “no reformers” restriction removed, all but two of the 36 seats on the new council were filled by reformers and they began going through the books.

Perhaps to no great surprise it was found the old council’s balance sheet didn’t. Far from showing the claimed credit of £1,028 it was actually £1,170 in debt.

To redress the matter, the reformers committed sacrilege.

They sold off the contents of the Guildhall wine cellars, including the old port which was the special glory of the aldermen and “special citizens”. It went by auction to the highest bidder and fetched 64 shillings per dozen bottles.

This wasn’t the first time the Corporation had been in debt either. In 1822 it had been obliged to borrow £50 each from 20 members to balance the books and in 1824 it was decided to suspend the mayor’s feasts, which was a very public admission something was financially up.

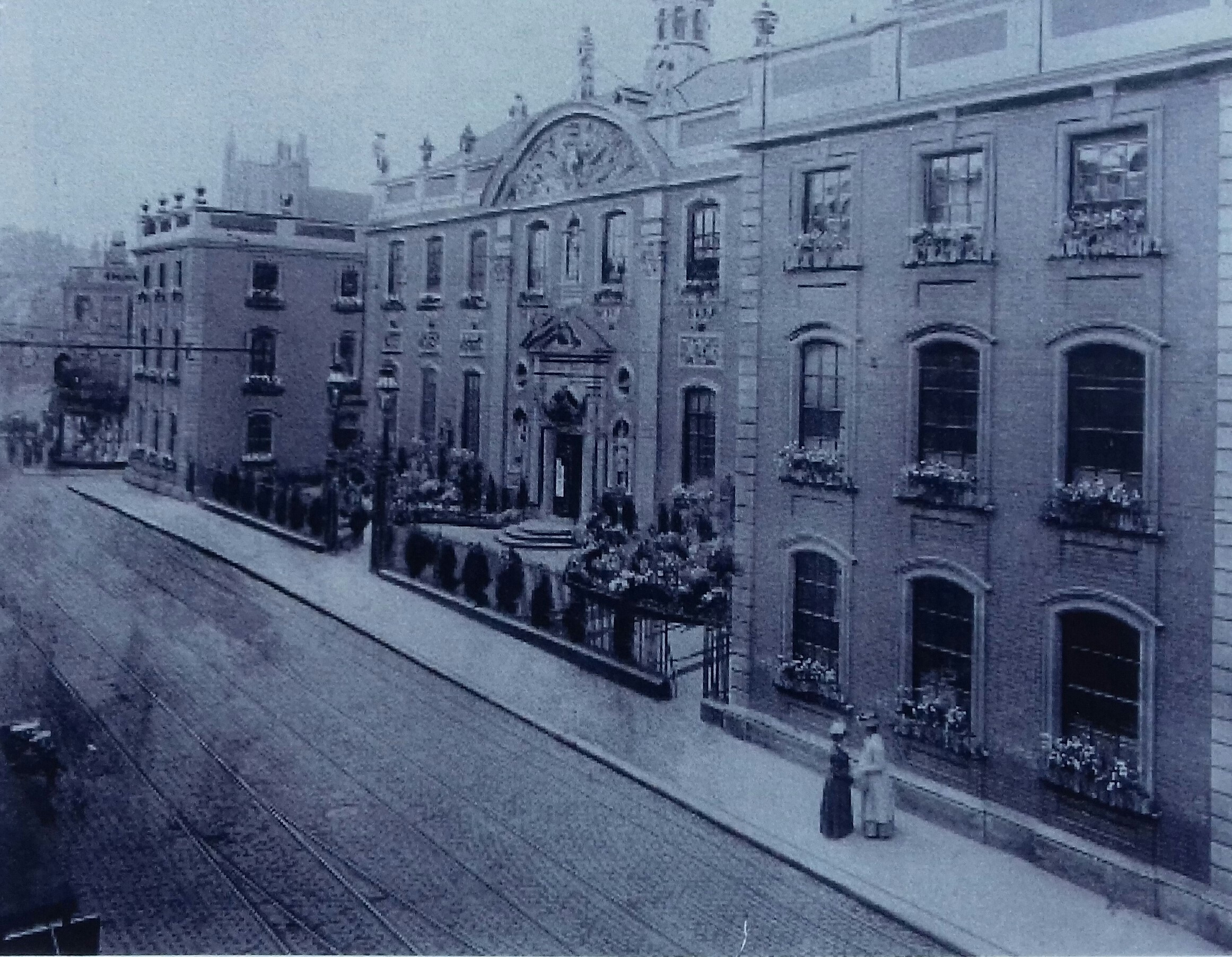

Worcester Guildhall in 1902 draped in bunting and flowers to mark the end of the Boer War.

However, one feature the Corporation did have in its favour was its HQ, the Guildhall in High Street, which when completed in 1723 was regarded as one of the finest civic buildings in the country.

It replaced a former wooden structure, but by the 1870s the new Guildhall had develop its own faults, leading to a massive restoration in 1880.

This resulted in the magnificent coved and richly ornamented ceiling in the Assembly Room still seen today. An example of money well spent.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel