NOW the UK seems, fingers crossed, to be getting on top of Covid-19, let’s go back nearly 200 years to when Worcester was really in the grip of a health panic.

In the 1830s, cholera swept through the city killing more than 150 people out of a total population of 13,000. A similar percentage today would bring around 1,130 deaths and remember that would be within the city limits alone.

The Beehive Inn on Tallow Hill, which closed in 2000 and was demolished. Nearby a mass grave was dug in the 1830s to bury Worcester’s victims of cholera

In the early 1800s, Worcester’s main cemetery was at the bottom of Tallow Hill and it was there a mass grave was dug to bury the cholera corpses.

The site was near the old Beehive Inn and although all trace of it above ground has long since disappeared, records show that in the 1920s a small wall still surrounded it.

Doctors at the time had been well aware of the spread of Asiatic cholera from India and a local medical team led by the eminent physician Dr Charles Hastings (founder of the British Medical Association) prepared for the worst.

Read more: Cocks to the rescue for British

Early in 1832 the first alarm came when 11-year-old Eliza Caldwell went down with symptoms very like those of cholera. The doctors examined young Eliza with some trepidation, but eventually diagnosed scarlet fever. But there as no doubt on July 14.

A travelling brazier and rag collector who lived in The Pinch, a particularly dirty area of Hylton Road, took ill and died within 16 hours. Now cholera had definitely arrived in Worcester.

Most of the cases occurred in The Pinch, where the disease continued to rage until early October. In all there were 293 cases and 79 deaths in the first wave.

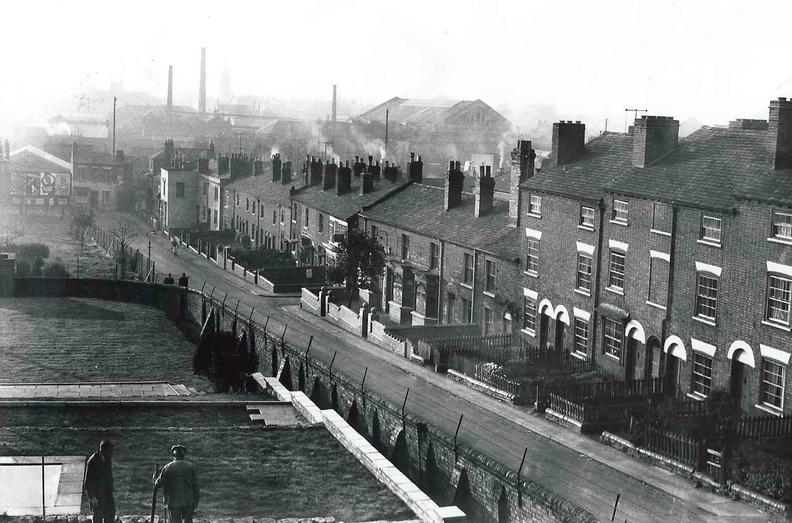

Flooding in Hylton Road, Worcester in 1910. The low lying ground near the river made it haven for cholera in the 19th century

Mind you, many of the local churchmen took a different view to the medics and put the deaths down to evil living. A theme echoed in one Worcester newspaper, which wrote: “Young man, drunk the night before, died of cholera next day.”

Then there was a woman in The Butts who died of malignant cholera. The jury returned a verdict of “Died by the Visitation of God” and the report added: “The deceased was between 30 and 40 years of age, she lived a very dissolute life and occasionally drank large quantities of gin.”

Even more dramatic was a story which ran: “At a meeting of the Ranters, or Primitive Methodists, in Tybridge Street, a young man about 20 years of age interrupted them with abusive and blasphemous language. He appeared quite well and sober, but a few hours later he was seized with cholera and by two o’clock the following afternoon he was a corpse.” In other words, abuse him and God will strike you down.

To cope with the plague, a special hospital was set up on Henwick Hill together with a “pesthouse”, while at Berwick’s Bridge, Diglis there was a “house of refuge”.

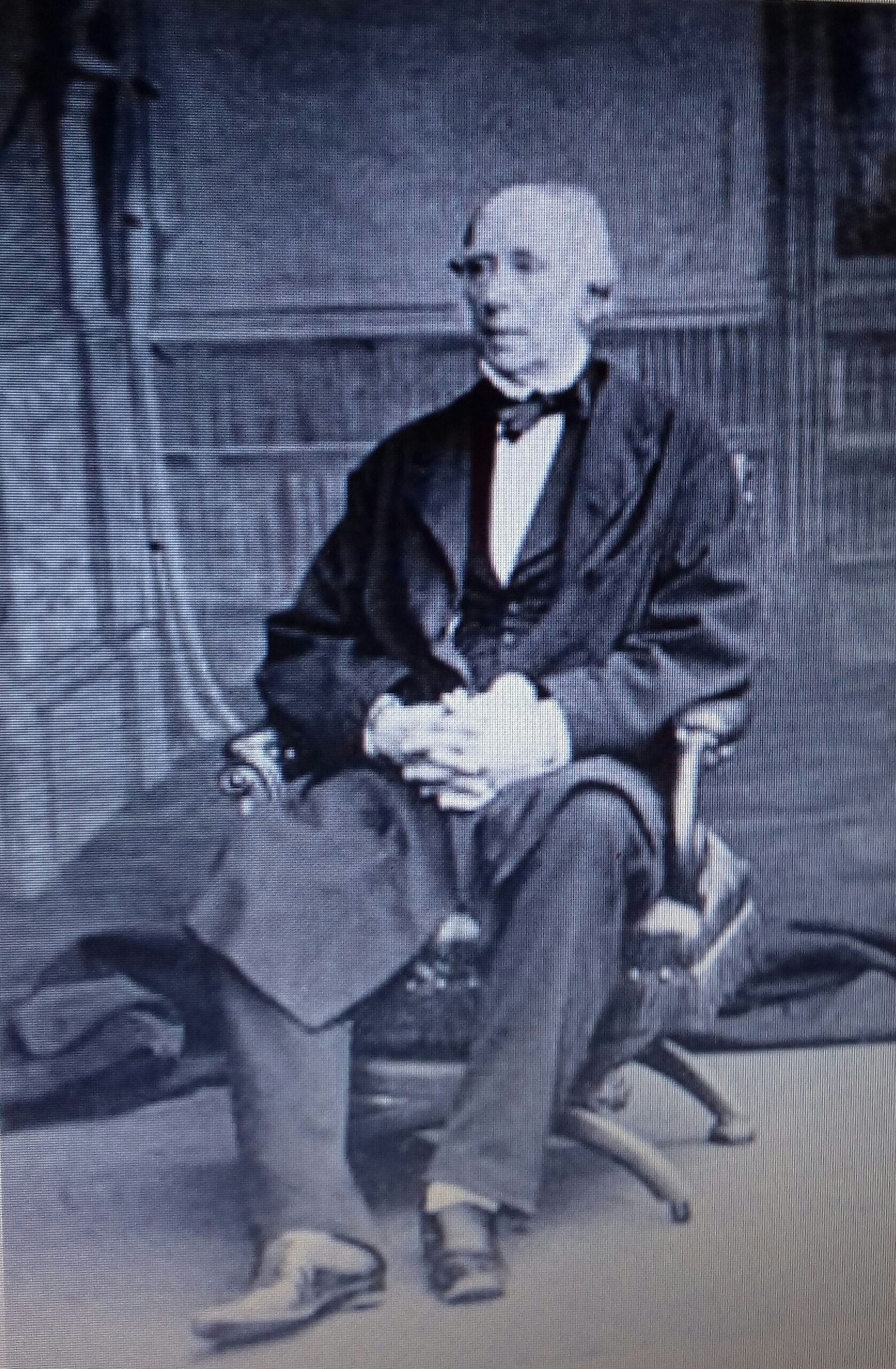

Dr Charles Hastings who led Worcester’s battle against cholera in the 1830s. He personally attended every case and supervised the burial of the dead

The health authorities ordered that victims of cholera should be buried within a day and under Dr Hastings’ guidance the people in low lying areas were encouraged to live in tents and shacks set up on Ronkswood Hill during the hot summer months.

Hastings was already familiar with the health problems suffered by those living in the low lying areas of the city, who were largely the poor, where drainage was bad and living conditions squalid and unhealthy.

He personally attended every case of cholera and saw to the speedy burial of the dead and the cleansing of unsanitary places.

Victorian flooding in Hylton Road shows how easily the water still entered the riverside houses

A second outbreak of the disease occurred in 1849 with 49 fatalities and a third in 1853, which had slightly less impact.

By then is was clear cholera was carried by dirty water and yet councillors who were in a panic when the outbreaks were at their height still fought against using the rates to supply clean water. It was not until 1872 that general sanitary legislation came into force.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel