Discover History’s Paul Harding continues his countdown to the 370th anniversary of the Battle of Worcester

AS hay was being harvested on the banks of the Severn and freshly dyed cloth swayed in the cool breeze on Pitchcroft Meadow, war clouds were beginning to gather in the north of England.

The Scots had been toying with the idea of fighting a war of hit-and-run attacks on the Parliament army of occupation or crossing the border and marching triumphantly into London to restore the monarchy for the Stuarts. The monarchy ended in 1649 with the execution of King Charles I.

On July 31 1651, the Royalists chose to leave Stirling, intent on slipping past Oliver Cromwell’s men and marching on London.

Charles had a choice of commanders for this campaign – and none of them worked well together.

George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham was the only Englishman of high rank, but having an English commander would not enthuse the largely Scottish army.

He was also seen by many as too young and inexperienced for such a large undertaking.

The Scotsman, General David Leslie was an extremely experienced cavalry commander, after fighting in the 30 Years’ War, the Bishops’ Wars and more recently the English Civil Wars.

Sir John Middleton was also considered, however in the end William, 2nd Duke of Hamilton became the favourite choice to bring about the victory that the Royalists craved.

Cromwell was a very calculating man and a few days after hearing of the Royalist march south, ordered General Lambert with 4,000 cavalry to shadow the enemy, but to not engage them.

For Cromwell to gain a final victory and to end the war completely, he knew his army must be much bigger than that of the Royalists.

This small Parliamentarian force was also instructed to report back the movements of the enemy and in particular any troops flocking to this cause.

By August 6 the Royalists crossed the border near Carlisle.

However not every Scotsman was eager to cross the border! Some men from the Macdonalds and the Cameron clans were very fearful that other clans may attack their farms in the Highlands.

They also feared that the New Model Army might burn their homes and imprison their kin left behind in Scotland. The Earl of Argyle openly thought the invasion of England would not end well.

As the Royalists crossed the border, the main Parliament field army under Cromwell left Leith and began to march south.

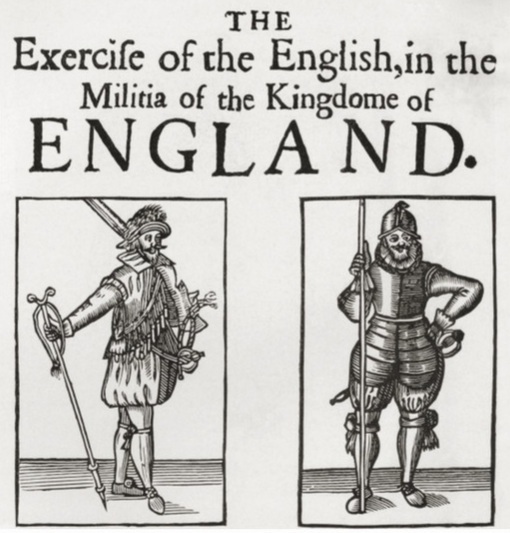

Training the Militias was done at a county level

At the same time the Northern Militias were ordered to muster under Major General Thomas Harrison, but not to engage any enemy.

Lambert’s shadowing force had to keep the Royalists on the western side of the Pennines to keep Charles from any access to London in the east.

The march through England was made at great speed in very hot weather. The Duke of Hamilton said: “All the Rogues have left us… I was not sure if it was out of fear or disloyalty.”

English towns saw the Scots as an invading Scottish army not a Royal one. Fear of a plundering army pushed more men into the militias which were gaining strength by the day.

On August 15 1651 Cromwell ordered the Northern Militias to link up with Lambert in the west.

This in turn led to a skirmish at Warrington, involving the Royalist Army trying to cross the River Mersey into Cheshire.

A force made up of some enthusiastic Cheshire Militia and the cavalry under Lambert blocked the bridge, but ended with the small Parliament force pulling back to the east.

Some historians say this was done to give the Royalists a little victory to ensure they continued deeper into England.

As we enjoy the summer holidays it’s hard to imagine that 370 years ago two armies, amounting to over 40,000 men, were on a collision course, and heading towards the Midlands. War was approaching Worcester again.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here