CONSIDERING in recent years it’s had a considerable connection with food of varying sorts, news that a plot of real estate at the bottom of Angel Street in central Worcester was probably not after all the site of a huge plague pit in the 17th century is only to be welcomed.

After all no one wants to be tucking into a plateful of anything to be suddenly asked: “What’s that strange smell? Seems a bit bubonic to me.” Cue rapid exit and a quick check for flea bites.

Worcester’s old pest house in Barbourne, originally an elegant Georgian property called Barbourne Lodge, was set on fire by order of the city council in 1905 and then demolished to allay any fears of lingering infection

The site at the junction of Angel Street and Angel Place, opposite the former Scala cinema, was traditionally an open space and the location of Worcester’s old sheep market until 1920 when a roofed structure was erected for a fruit and vegetable market. It later became a shopping/small business arcade, a couple of eateries and is now empty awaiting the next brave soul.

The old Corn Exchange building in Angel Street in the 1970s. In its chequered history it has also been an auction room, boxing arena, carpet warehouse and a branch of Habitat

The age old reluctance to build on this bit of land – after all there were plenty of properties surrounding it in the 1920s – probably came from the long-held view it covered a pit used for mass burials during the last outbreak of bubonic plague in Worcester in 1637.

The interior of the old Scala cinema in 1973

Plague spores seeping out of the ground centuries later would make a good Hammer horror film. Cue Christopher Lee as the mad scientist who sets up a lab there and Caroline Munro as his glamorous and unwitting visitor.

Thankfully that’s likely fantasy. For a start the site was within the city walls, when plague pits were normally dug outside, well away from the population, and although the burial pit was first mooted in 1624 as a solution to the very real problem of the cathedral cemetery being full to overflowing, it was not consecrated until 1644, seven years after the plague had run its course locally.

Those were the days before mass TV when Tarzan turning up in Worcester attracted a crowd. Although he was a bit short of creepers to swing over Angel Street for a swift half in the Horn and Trumpet

Of course there is always the possibility such a disaster called for hasty measures, including the use of unconsecrated ground, because there’s no doubt those were desperate times, the worst Worcester has faced outside of war. At least one-fifth of the population died – 1,551 victims were buried, of whom 236 were from St Andrew’s parish.

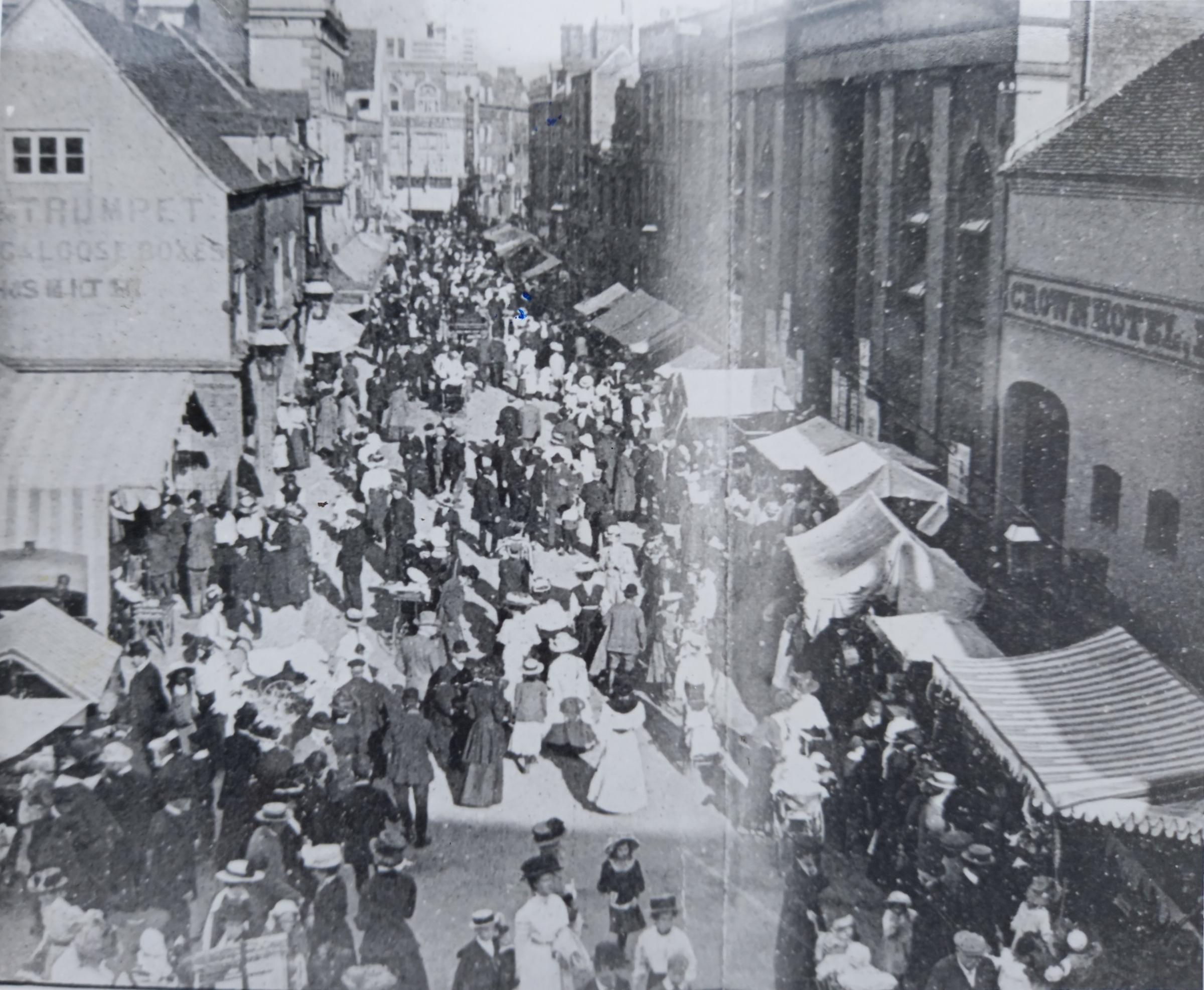

A Worcester Fayre day in Angel Street in the early 1900s. Obviously a possible plague in the locality was no deterrent

All who could do so fled the city, but most were refused shelter elsewhere and were forced to create a camp at Bevere. Both fugitives and those who remained within the city walls faced starvation, because country folk feared the infection and were reluctant to help. But for the courage and charity of a few, many city dwellers would have died of hunger not the plague.

But there is a third reason which makes a plague pit at the bottom of Angel Street unlikely. Just to the west of the site was a substantial house belonging to George Hemming, a man of considerable social standing and later a member of the city corporation. While to the east a gentleman named Robert Sterrop built an even larger house in 1646, the year before he became mayor.

Looking down Angel Place before it got knocked about a bit

Human nature being what it is, it’s hard to imagine either of these two city stalwarts choosing to live next to a plague pit. Not a very appetising topic for after dinner conversation.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel