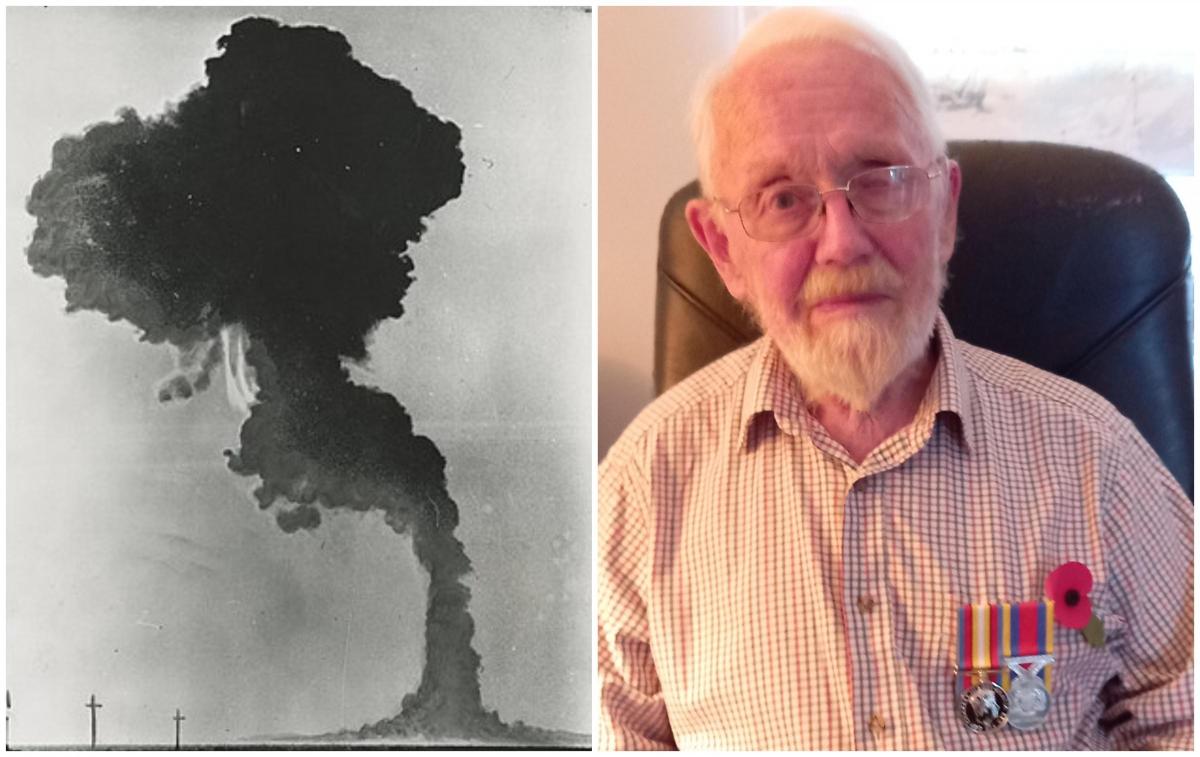

IN the military sometimes just standing still is the hard part and 70 years on David Phillips has at last been awarded a medal for standing still in the vicinity of an atomic explosion.

The episode took place in 1953 on desert scrub land in Australia as the UK took steady steps into the nuclear arms age. Disregarding the Old Soldier’s motto of Never Volunteer, David had asked to be included in a group of RAF personnel to witness the detonating of one of Britain’s first atomic bombs.

Knowing what we know today, some of us might not have done that, but young David was up for the experience and now at the age of 90, his Nuclear Test Medal has finally arrived. Courtesy of Boris Johnson who pushed for it during his tenure as PM.

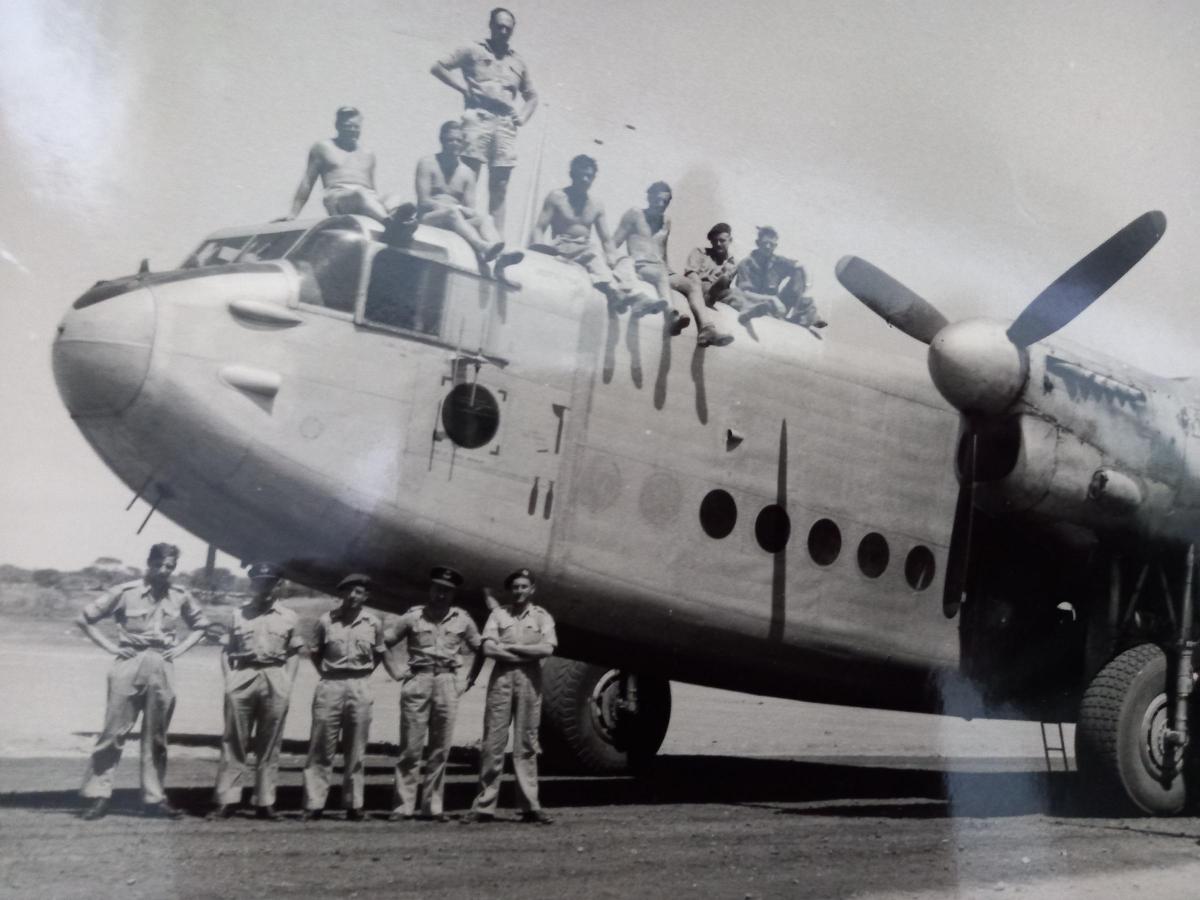

Born in Birmingham, but since 1963 resident in Elmley Castle, near Pershore, David served 12 years as an RAF pilot and was in a unit tasked with ferrying supplies and equipment to a proposed nuclear test site 300 miles into the desert from Woomera at Emu Field in South Australia.

He explained: “We flew a daily schedule and it was a pretty punishing task for both crews and aircraft. After six months they were ready to explode the first bomb and having put in so much work we asked if we could witness the test.”

At this point it must be added that Dr William Penny, the chief scientist, only agreed with some reluctance.

David continued: “We were nine miles from ground zero. The bomb was mounted at the top of a steel tower about a hundred feet high. There was a straight road leading from the main site and at its end we could just make out the tower glinting in the morning sun. After the preliminaries, we were instructed over a loudspeaker to face away from the bomb and shut our eyes. Then the countdown began.

“We knew the bomb had exploded because we could feel a pulse of heat on our backs, but even more startling was that even through closed eyes we could see the sky had lit up. For second we were aware of the veins in our eyelids.

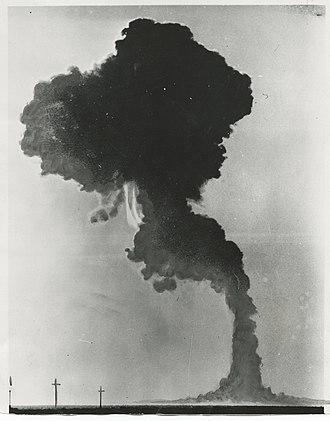

“Now we could turn around and the sight was awesome. A huge glowing fireball about a quarter of a mile across was sitting on the desert floor. As we watched it slowly lifted into the sky like a giant balloon. Eventually the whole ball turned white with a white tail trailing below forming the familiar mushroom cloud which became one of the icons of the twentieth century.”

To get a better view, David and a companion climbed onto the bonnet of a Land Rover.

“The cloud rose, towering above us,” he recalled. “There was complete silence. No-one spoke, we were all overawed by the immensity of the occasion. As I continued to watch I was aware of a wall of dust moving along the road towards us. Suddenly there was an almighty bang. We were nearly knocked off the Land Rover as the blast hit us.

“The heat radiation had travelled at the speed of light but the sound had only travelled at, well the speed of sound. To cover nine miles it had taken about fifty seconds. Now the blast had hit us the spell was broken. Everyone started talking and laughing; there was general uproar.”

As David and the RAF team left the base they flew low over the test site. There was no steel tower. It had been completely vaporised by the explosion. The blast had also fused the desert sand into glass like a giant ice rink. “Sometimes I wonder if that glass circle us still there,” he mused.

Three years later Flying Officer Phillips also witnessed the testing of Britain’s first hydrogen bomb on Christmas Island and on leaving the RAF enjoyed a long and successful career as an electrical wholesaler.

He said: “I have never had any repercussions from witnessing the tests.” And 70 years later he’s still giving talks about his experience.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here