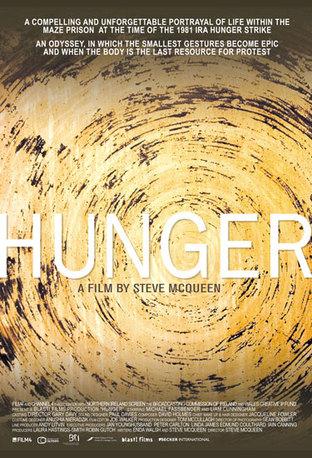

Let’s get this out of the way early: Hunger is a hard watch. Mining still sensitive issues and watching a slow, agonising death of IRA prisoner Bobby Sands (Michael Fassbender) on hunger strike (sorry for the spoiler – it is a docudrama) is hardly ideal viewing for most audiences. This combined with director Steve McQueen’s ‘arty’ film style which lets the camera do the talking, makes it all seem depressingly dull and too bleak for mainstream audiences. Ironically enough that’s the film’s main strength. Docudrama doesn’t come into your head, the film transcends that.

The film takes its time getting to Sands and instead we follow prison guards and other prisoners and how the prison revolves around their lives. McQueen unleashes his artistic background here; long takes, many without dialogue of disgusting, repulsive imagery filmed with such nuance by Sean Bobbit that the film finds something beautiful in them. One particular scene sees a prison guard mop up piss for five minutes. Strangely hypnotic, it transcends simple artful imagery because it always has something to say. It is also surprising to see a director’s first feature be so technically adept, early on in the film McQueen intercuts between prison guard Raymond Lohan (Stuart Graham) and inmates Gerry Campbell (Liam McMahon) and Davey Gillen (Brian Milligan) with ease.

Many critics who saw the film were quick to lash out at McQueen’s questionable motives: Does he sympathise with the IRA by having the audience become committed witnesses to his dying cause? I think not. McQueen confidently positions the audience with several characters throughout. The films starts with the audience positioned with a prison guard who we later are distanced from due to his actions. McQueen also positions us with riot guards, a doctor and Sands' parents; this eliminates the simple pro or anti IRA argument and instead provides a human detailed element. McQueen is also quick to remind us that the prisoners are terrorists and by staging a brutal murder of a prison guard in the most callous of places, it keeps the audience off balance with whom to actually side with. The camera also lingers on human pain and suffering; handheld close ups of Sands getting his hair and chunks of his head cut and the brutal beatings of prisoners by the prison guards and their truncheons, McQueen refuses to spare any details.

However it’s the astounding eighteen minute take of a conversation between Sands and his priest that is the moral centre of the film. This scene manages to give arguments for and against Sands’ hunger strike and the audacious take is used to channel the audience’s attention on what is said. In the end it is clear that the film is not pro or anti IRA but instead explores why a young man, who is intelligent should condemn himself to a painful death. By having the conversation with a priest it creates the faith dynamic of men dying for a cause they believe so strongly in.

The final third of the film painstakingly follows Sands' hunger strike. The camera mainly focuses on Sands' deteriorating body, it is very convincing and grim but nevertheless it results in absolute attentiveness. Michael Fassbender is brilliant in his role, not just for losing a dangerous amount of weight but for playing his role with conviction. McQueen is someone to keep tabs on because with his first effort he has managed to make an art film that tells such an important and human story. It is audacious and exciting filmmaking.

People who see the film will continue to debate its motives and representation of terrorists however the fact that Hunger is powerful and provoking enough to prompt such discussion is merit to its fascinating ability to commit to such a delicate subject. Hunger is one of the memorable and unremittingly bleak films of the decade.

- This review was submitted by a reader. Submit yours in the 'reviews' section of our forums here.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here