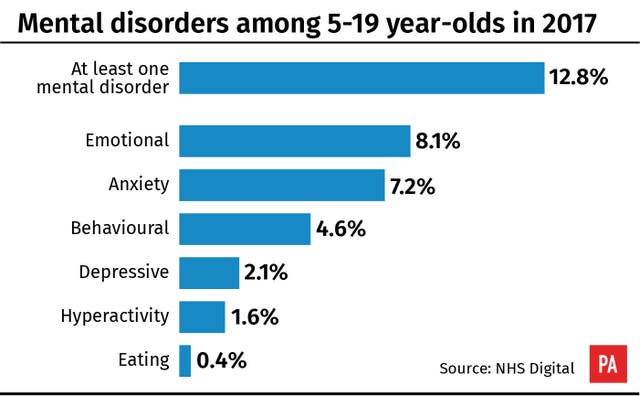

One in eight children and young people aged between five and 19 had a mental disorder in England in 2017, according to a major report.

NHS Digital, which collected information from more than 9,000 youngsters, also found emotional disorders have become more common in five to 15-year-olds – rising from 4.3% in 1999 to 5.8% in 2017.

Looking at the five to 15-year-old age group over time, the report reveals a slight increase in the overall prevalence of mental disorder, increasing from 9.7% in 1999 and 10.1% in 2004, to 11.2% in 2017.

When including five to 19-year-olds, the 2017 prevalence is 12.8%, but it said this cannot be compared with earlier years as it is the first time the survey has covered youngsters up to the age of 19.

Previously it focused only on the five to 15-year-old age group.

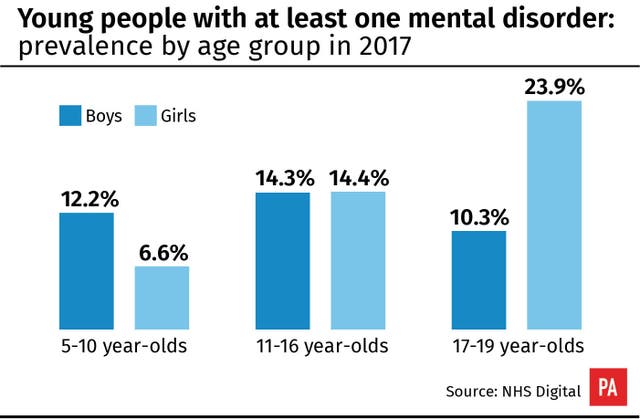

Meanwhile one in six (16.9%) 17 to 19-year-olds were found to have a mental disorder, with one in 16 (6.4%) experiencing more than one mental disorder at the time of the interview.

Females aged 17 to 19 were more than twice as likely as males of the same age to have a mental disorder.

Females aged 17 to 19 were more than twice as likely as boys to have a mental disorder. Find out more in our newest #MentalHealth of Children and Young People in England, 2017 report: https://t.co/uLsN7d0riy pic.twitter.com/TyhOMExyxl

— NHS Digital (@NHSDigital) November 22, 2018

One in 18 (5.5%) preschool children were identified as having at least one mental disorder at the time they were surveyed.

Teenagers aged 14 to 19 years old who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual or with another sexual identity, were more than twice as likely (34.9%) to have a mental disorder, as opposed to those who identified as heterosexual (13.2%).

A quarter (25.5%) of 11 to 16-year-olds with a mental disorder had self-harmed or attempted suicide at some point, compared to 3% of those who were not diagnosed as having a mental disorder.

In 17 to 19-year-olds with a mental disorder, nearly half (46.8%) had self harmed or made a suicide attempt.

We welcome new insights from @NHSDigital into young people's #mentalhealth so that suicide prevention expertise and resources can be targeted at those most at risk. https://t.co/R1SFI6d13c

— Samaritans (@samaritans) November 22, 2018

Denise Hatton, chief executive of YMCA England & Wales, described the figures as a “wake-up call”.

She said: “These figures are shocking and while progress has been made to normalise conversations about mental health and successive governments have made additional funding for NHS services available, today’s figures are a wake-up call that this clearly hasn’t gone far enough.

“To end this crisis that is ruining young lives, it’s crucial that action and investment goes into preventing young people from experiencing poor mental health in the first place.

“From preventative youth and community services, to education in schools, mental health must be incorporated in every aspect of daily life to stop young people from reaching crisis point.

“Without preventative services and with the NHS struggling to cope, too many young people are still left alone to deal with their mental health difficulties by themselves, leading to a vicious circle of solitude and suffering.”

Lily Makurah, national lead for mental health at Public Health England, said: “It’s concerning to see children and young people facing mental health challenges.

“We know mental health influences children’s ability to cope with the normal stresses of life, to learn productively, to develop positive relationships and to make a contribution to our community.

“We’re working with partners to minimise risks for children and young people and enhance factors that promote and protect positive mental health at key stages across a child’s life.”

Young women aged 17 to 19 were identified as having higher rates of emotional disorder and self-harm than other groups.

Nearly one in four (23.9%) had a mental disorder and 22.4% had an emotional disorder, the figures show.

Sarah Hughes, from the charity Centre for Mental Health, said emotional difficulties have risen significantly since the last survey in 2004, while other conditions have remained stable.

“Today’s survey results underline the case for a comprehensive approach to improving children’s mental health,” she added.

“Childhood mental health difficulties are inextricably linked to social and economic inequalities, the adversities children encounter and the environments they live in.

“We know that poverty, inequality and housing insecurity are closely linked with childhood mental health difficulties so we need to see concerted action to reduce these nationwide.

“Today’s survey shows that children in low-income households are more than twice as likely to have a mental health problem as those in higher income households.

“We need a whole Government strategy to bring about system change nationwide and support local authorities, the voluntary sector, schools, families and children and young people themselves to make a difference in their communities.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here