WE are only a few months into the centenary commemorations, but already the nation's look back at the First World War has produced a number of remarkable books.

One of the most relevant locally is Worcestershire's War, published by Amberley as one of its Voices of the First World War series and the work of three Worcester-based historians. Adrian Gregson, who works from The Hive history centre, manages the archives for Worcestershire County Council and has a particular interest in the Great War, Maggie Andrews is a lecturer at the University of Worcester, specialising in 20th century social and cultural history, and John Peters also lectures at the university and teaches First World War history.

Between them they have spent a year trawling through letters, diaries and journals of the time to collate a comprehensive account of how Worcestershire experienced, and survived, the war.

"I think it's important to point out that the First World War was not all about the Tommies fighting in the trenches," Dr Gregson said. "Of course that was a vital part, but there were many other aspects which must never be forgotten. Like the fighting in the Middle East, the struggles on the home front and the huge impact the war had on the development of the medical profession."

The war also gave birth to the Women's Land Army and a massive lift to the cause of female emancipation. More women were doing jobs that were traditionally the preserve of men and society was on an unstoppable change. At a meeting of Worcestershire War Agricultural Executive Committee, Mr James Woodyatt, chairman of the Malvern District Council sub-committee, argued that these were no days for snobbery, honest labour was no disgrace to a man or woman and an expert workman was an honour to his country. Any gentleman or lady, whatever their position, who did a day's work on the land ought to be paid. He did not believe the farmer should get gratuitous labour either. If a woman did a man's work she ought to get a man's wages.

However, this presented the problem of what to do with the children while mothers worked. Some women, it appears, were criticised for not wanting to leave their children, while others seemed rather too willing to do so.

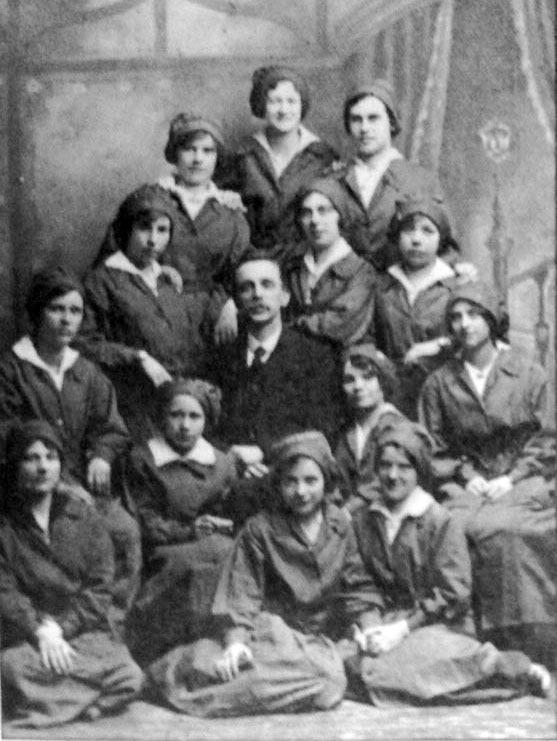

One of the less publicised operations - for rather obvious reasons - was the large munitions factory that grew up in the Blackpole area of Worcester as the war developed. By 1918 the Blackpole Munitions Works was despatching nearly three million cartridges a week and although it was supposed to be secret, pictures of its women workers often featured in the local press. As did a report that the local Baptists Women's League had become rather concerned about the munitions girls swearing. Apparently their "leisure activities" caused concern too but were curtailed by government regulations on pub opening hours and the strength of beer.

When the end of the war was announced, wounded soldiers in Battenhall Hospital - the large private house Mount Battenhall, which later became St Mary's Convent School - banged their mess tins in excitement, while in Malvern there was a march through the town with music played on drums and combs.

And then reality struck home as Colonel Chichester from Norton Barracks wrote to Berrow's Worcester Journal asking for anyone to give "games, playing cards, cigarettes, newspapers and periodicals" for the 600 wounded men he had in his care. The First World War changed life in Worcestershire for everyone forever.

Worcestershire's War by Maggie Andrews, Adrian Gregson and John Peters is published by Amberley at £14.99

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here